Last week, we discussed the Earth’s three different types of rock, and we can hardly talk about rocks without also discussing minerals. After all, the vast majority of rocks contain one or more minerals within them. A mineral is defined as a naturally occurring substance with distinctive chemical and physical properties, compositions, and atomic structures.

For this article, we will use the Dana Classification System of minerals. This system originally listed nine main mineral classes: Native Elements, Sulfides, Sulfates, Halides, Oxides, Carbonates, Phosphates, Silicates, and Organic Minerals. Our classification system has continued to grow and develop over the years, such that today there are 78 recognized mineral classes. However, as it would take too much space to describe all 78, we’ll stick with the original nine.

Native elements

You are probably familiar with the native elements as they appear on the Periodic Table of Elements. Native elements are any of a number of chemical elements that may occur in nature uncombined with other elements. (Elements that occur as atmospheric gasses are excluded from this category.)

Of the 90 chemical elements found in nature, only 19 are known to occur as minerals. These are usually divided into three groups:

- Metals: platinum, iridium, osmium, iron, zinc, tin, gold, silver, copper, mercury, lead, chromium;

- Semimetals: bismuth, antimony, arsenic, tellurium, selenium;

- Nonmetals: sulfur, carbon.

It is essentially impossible to generalize about the geological occurrences of the native elements, as their formation processes vary greatly and they are found in all types of rocks. For instance, native iron (kamacite) is found primarily in meteorites, while terrestrial native iron is considerably more rare, found in small amounts in igneous rocks (basalts), carbonaceous sedimentary rocks, and petrified wood. Many other metals and some nonmetals are abundant enough to form deposits of commercial importance. Native gold and silver, for example, are the principal ores of native metals and are found all over the world.

Sulfides

Sulfide minerals are compounds of sulfur with one or more metals. Most sulfides are structurally simple, highly symmetrical in their crystal forms, and have many metallic properties (including metallic luster and electrical conductivity). They often bear striking colors and possess a low hardness and a high specific gravity.

Sulfides occur in all rock types and are the source of various precious metals (most notably gold, silver, and platinum). A few examples of sulfide minerals include galena, chalcopyrite, pyrite, sphalerite, marcasite, and realgar.

Sulfates

Sulfate minerals are naturally occurring salts of sulfuric acid (H2SO4). There are about 200 distinct kinds of sulfates recorded in mineralogical literature, but the majority of them are rare and of local occurrence. What sulfate minerals are abundant (barite, celestite, etc) are used heavily in industry. Beds of sulfate minerals are often mined for fertilizer and salt preparations, and pure gypsum beds are mined to make alabaster.

Well-known examples of sulfate minerals include gypsum (satin spar and selenite), celestite, and barite.

Halides

Halide minerals are naturally occurring inorganic compounds that are salts of the halogen acids (e.g., hydrochloric acid). Most of these compounds are rare and of extremely local occurrence (with the exceptions of halite, sylvite, and fluorite). Most halides are soluble in water, and transition-metal halides are unstable when exposed to air.

The most commonly referenced example of a halide mineral is halite, or sodium chloride (NaCI). Halite frequently occurs with other evaporite minerals in enormous beds that are the post-evaporation result of the accumulation of brines and trapped ocean water. Sylvite, or potassium chloride (KCI), is also sometimes present in such beds. Fluorite, or calcium fluoride (CaF2) is another well-known halide, and is found in limestones that have been exposed to aqueous solutions containing the fluoride anion.

Some examples of halide minerals include halite, fluorite, sylvite, marshite, calomel, and zavaritskite.

Oxides

Oxide minerals are naturally occurring compounds wherein oxygen is combined with one or more metals (e.g., iron, manganese, aluminum, chromium, titanium, or copper). This mineral group is famous for its distinct physical properties, including high hardness and density, moderate to high luster, and refractory nature. The majority of oxides are stable in most geological environments as well as in the surface environment. They are found as primary minerals in igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rock types.

Oxide minerals are extremely diverse and encompass many mineral species. Some examples are corundum, hematite, ice (yes, ice!), rutile, spinel, brucite, and goethite.

Carbonates

Carbonate minerals are based on—you guessed it!—the native element carbon. This element is one of the most important on earth, since it forms thousands of useful compounds. Life as we know it would not exist without carbon. However, it is also a fickle element; for instance, when combined with rain, it forms acid rain.

In the Periodic Table of Native Elements, carbon belongs to an unusual vertical group. Each of the elements in this group has an outer valence electron shell of four electrons that can share or loan and four vacancies that can form compounds. This essentially means that carbon can take in or loan electrons, an ability that forms the basis for all carbonate minerals and thousands of hydrocarbon minerals.

A few noteworthy examples of carbonate minerals include calcite, dolomite, aragonite, smithsonite, malachite, azurite, and rhodochrosite.

Phosphates

Phosphate minerals are naturally occurring inorganic salts of phosphoric acid, or H3(PO4). There are more than 200 recognized species of phosphate minerals. Structurally, they all have isolated tetrahedral units.

Phosphates fall into three categories:

- Primary phosphates that have crystallized from a liquid (examples: apatite, triphylite, and lithiophilite);

- Secondary phosphates formed when primary phosphates are altered (examples: lazulite, turquoise, and vivianite);

- Fine-grained rock phosphates formed at low temperatures from organic material containing phosphorus, which primarily happens underwater (examples: hydroxyl-apatite, carbonate-apatite, and fluor-apatite).

Silicates

Silicate minerals are rock-forming minerals that are composed of silicate groups. This class of minerals is the largest and most important in the world, making up about 90% of the Earth’s crust.

In mineralogy, silica (silicon dioxide, SiO2) is ordinarily considered a silicate mineral instead of an oxide mineral. Silica in nature presents as the mineral quartz and its polymorphs. A wide variety of silicate minerals occur on our planet, and they occur in an even wider range of combinations. This is because of the processes involved in their formation (including partial melting, crystallization, fractionation, metamorphism, weathering, and diagenesis), which have been re-working the crust for billions of years.

The most familiar types of silicate minerals include beryls (emerald, aquamarine, morganite, etc); tourmalines; feldspars (labradorite, moonstone, etc); garnet; epidote; serpentine; mica; and, of course, quartz. There are many, many more silicate mineral types than are listed here.

Quartz in particular is an extremely well-known silicate mineral. There are nearly countless forms and polymorphs of quartz. In fact, a lot of crystal lovers are unfamiliar with what falls under the quartz umbrella. Here is a helpful bullet list showing some of the most popular varieties of quartz:

- Quartz: the mama crystal!

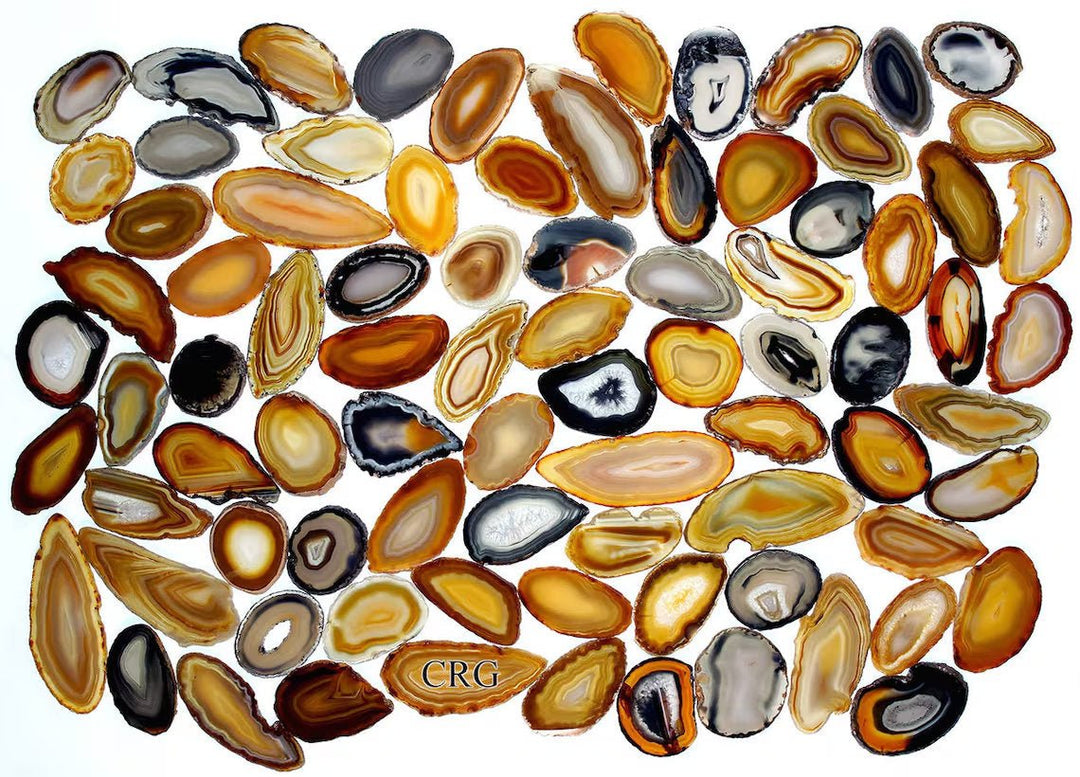

- Chalcedony: a finely crystallized or fibrous quartz.

- Jasper: an aggregate of microgranular quartz and/or cryptocrystalline chalcedony and other mineral phases.

- Citrine: a variety of quartz that forms when amethyst or smoky quartz are heated, whether artificially or by the Earth's crust, to temperatures of about 800-900F (426-482C) or more.

- Amethyst: a variety of quartz that gets its purple color from iron impurities.

- Smoky quartz: a variety of quartz whose smoky color is produced when natural radiation from surrounding rock activates color around aluminum impurities within the quartz.

- Aventurine: a variety of quartz with a distinctive shimmering or glittering effect caused by inclusions such as mica, hematite, or fuchsite.

- Flint: a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz.

- Tiger's eye: a variety of quartz that exhibits a unique optical phenomenon called chatoyancy, or cat's eye effect.

Organic minerals

Organic minerals are compounds containing carbon, and they form as a result of biological processes. There are three classes of organic mineral:

- Hydrocarbons, which contain just hydrogen and carbon;

- Salts of organic acids, in which an organic acid is combined with a base;

- Miscellaneous, or any organic mineral that does not fall in either of the other categories.

Organic minerals are rare and usually have specialized settings (like fossilized cacti and bat guano). Mineralogists have predicted that there are more undiscovered organic mineral species than known ones. Known organic minerals include amber, pearls, coral, and coal.

So many minerals, so little time!

Understanding the nine main mineral types can feel like a daunting task, and we hope we’ve made it easier by compiling this handy list. If you have any questions about a specific mineral that isn't listed here, please don't hesitate to contact us at shop@crystalrivergems.com!